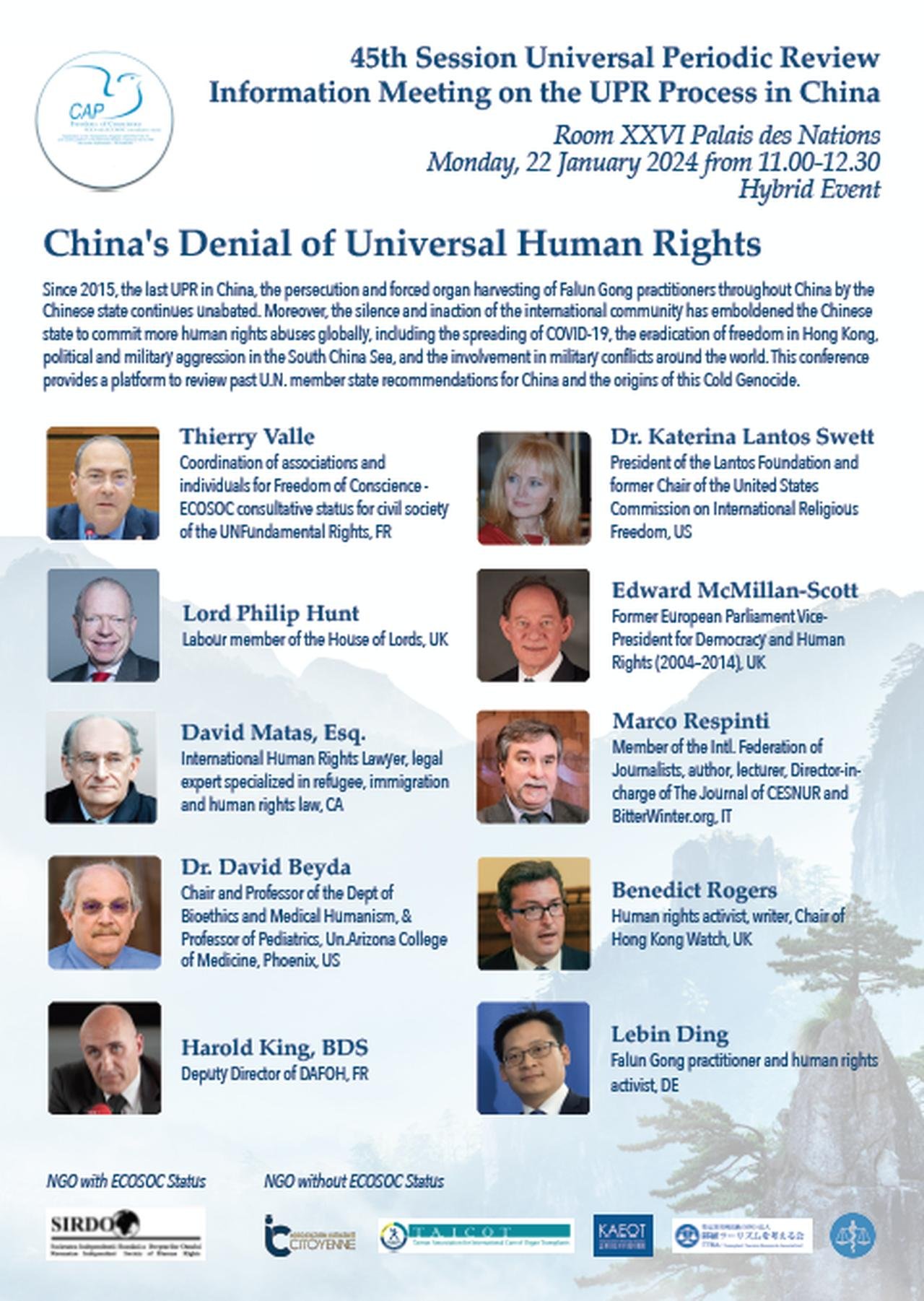

Hybrid Event by CAP Freedom of Conscience, a secular European NGO with United Nations Consultative Status

Conference online: https://www.ganjingworld.com/live/1gfhddgebsf1GPtTABokszqwj15v1c

Universal Periodic Review and China

by David Matas, International Human Rights Lawyer

27 January 2024

Next steps

1) Although it will be several years before the turn of China again comes up at Universal Periodic Review, the travesty of the Review this year highlights the need to reform the Review procedure. One simple reform would be joint government statements.

It is commonplace for NGOs to make joint submissions for the Universal Periodic Review. For the 2024 Universal Periodic Review for China, there were forty joint NGO submissions summarized in the UN Summary of Stakeholders Submissions.

Joint government oral statements are a way of circumventing the gaming of the system we saw with the Chinese Universal Periodic Review. With joint government oral statements, those countries who are serious about respect for human rights could, with each joint statement, take up a different human rights issue. Repetition could be avoided and the time available for serious human rights presentations could be best used.

Joint government statements are a commonplace of the United Nations Human Rights Council regular and special sessions. In principle, there should be no obstacle to introducing them into the Universal Periodic Review.

2) Something more immediate, when it comes to China, would be directing attention to the regular sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council. There are three such sessions a year, in late February and March, June and early July and September and early October. Every session has an agenda item titled "General Debate on Human Rights Situations that Require the Council's Attention".

Organ transplant abuse can be raised by any member state of the United Nations during any regular Council session during discussion on that agenda item. That agenda item is a more propitious opportunity than the Universal Periodic Review to raise concerns about human rights abuses in China, including the mass killing of prisoners of conscience for their organs, because of the frequency of the opportunity.

3) There is also the power the United Nations Human Rights Council has to hold a special debate or convene a special session on a particular subject. At the UN Human Rights Council session of September and early October 2022, a resolution to hold at the next regular session of the Council a debate on the situation of human rights in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region was co-sponsored by twenty-six states and defeated by a vote of 17 to 19 with eleven abstentions.

The reason that the vote in favour was less than the number of co-sponsoring states is that a state not member of the Council can co-sponsor a resolution, but not vote on a resolution. Of the twenty-six co-sponsors, only nine were Council members.

Although the resolution was defeated, it carried a message and had an impact. The majority of the Council did not vote against the resolution. The resolution failed only because of the number of abstentions. This technique, presenting at a regular session of the Council a resolution for a debate or a special session on forced organ harvesting in China, would be useful to raise awareness and concern about the abuse even if the resolution, for geo-political reasons, fails.

4) Another vehicle for information, investigation, advocacy and remedy within the UN Human Rights Council system is the appointment of either a country specific or thematic mechanism. Right now there are forty-five thematic mechanisms and thirteen country mechanisms which have been established by the Council.

The Council, for instance, in October 2022, created a special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Russian Federation. There is no reason why the Council could not also mandate a special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in China or a thematic mechanism, a special rapporteur, on organ transplant abuse.[1]

5) The response of the Government of China in August 2021 was unresponsive to the requests and concerns of the UN human rights experts of June 2021.[2] The experts should say so. They should follow up with a recommendation for an independent UN based investigation into organ transplant in China. That investigation should occur ideally with Government of China cooperation. In its absence, an investigation should be conducted nonetheless.

6) In August 2013, the Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children, at the time Joy Ngozi Ezeilo, produced a thematic analysis of the issue of trafficking in persons for the removal of organs.[3]

The Rapporteur in 2013 wrote:

"31. A very different picture of organ 'trade' involves the harvesting by the State of organs of persons who have been or are being executed. Allegations of such practices have been levelled at a number of countries, including in East Asia, from where consistent and credible evidence has emerged."

The footnote associated with that statement was this:

“See David Matas and Torsten Trey, eds., State Organs: Transplant Abuse in China (Woodstock, Ontario, Seraphim Editions, 2012). See also Mingxu Wang and Xueliang Wang, 'Organ donation by capital prisoners in China: reflections in Confucian ethics', Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, vol. 35, No. 2 (2010), pp. 197‑212; and G. M. Danovitch, M. E. Shapiro and J. Lavee, 'The use of executed prisoners as a source of organ transplants in China must stop', American Journal of Transplantation, vol. 11, No. 3 (2011), pp. 426‑428.”

The current Rapporteur is Siobhἀn Mullally, the Established Professor of Human Rights Law and Director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the School of Law, National University of Ireland, Galway.[4] Ms. Mullally was one of the twelve UN human rights experts who made the 2021 joint statement, mentioned earlier in this text, expressing concerns and alarm about reports of forced organ harvesting in China. She could be asked to address the scourge of forced organ harvesting in China in detail in one of her annual reports to the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Conclusion

The Universal Periodic Review is not the be all and end all for human rights accountability. There are other recourses within the UN human rights system which are more frequent, more accessible and more easily mobilized. The failure of the Universal Periodic Review for China to hold China to account for its human rights abuses, in particular the failure to address the mass killing of prisoners of conscience for their organs, should lead those concerned about Chinese abuses generally and this abuse in particular to invoke the other recourses available.

[1] https://documents‑dds‑ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/416/82/PDF/N1341682.pdf?OpenElement

[2] In addition to the comments above, see https://endtransplantabuse.org/press-release-china-issues-inadequate-and-misleading-response-to-un-correspondence-on-forced-organ-harvesting/

[3] https://documents‑dds‑ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/416/82/PDF/N1341682.pdf?OpenElement